Cliff Brown

In the summer of 2013 I finally left employment so I could work full time on turning 633 Engineering into a living; so I could be my own boss, set my own targets and primarily so I could build the best guitar amplifiers with no compromises. I've been a guitarist for around 40 years and working with electronics for 39. I love doing both - I guess it's the left brain and right brain in equal measures.

I've designed live sound mixers in Potters Bar, built and maintained professional recording studios in Willesden and Chelsea, repaired amps in Denmark Street, installed broadcast consoles in the World Trade Centre, and designed award winning guitar amplifiers for one of the biggest names around today.

I've also gigged and recorded regularly since the age of 12, playing rock, blues, jazz and country; and all styles in between. I've played on big stages and in small pubs. I've played at the Albert Hall and at Glastonbury.

I first got turned on to the electric guitar hearing Barney Kessel on my Dad's jazz records. Unlike most jazz guitarists, Barney would bend notes and sometimes had, possibly unintentionally, a little bit of distortion in his sound, and he often played quite bluesy licks. I also remember hearing tracks from an LP my Aunt had called 'Out Came The Blues' by Lightning Hopkins, Georgia White, Cousin Joe and others which had this wonderful electric guitar all over it. I definitely found the sound of blues electric guitar exciting.

I think I was ten or eleven when I built my first 'electric' guitar. It was a Spanish guitar with nylon strings and I had taped a small loudspeaker which had been removed from a broken TV onto the front of the guitar and using it in reverse as a microphone wired it into the mic input on my Dad's Grundig reel to reel tape recorder (complete with 'Magic Eye').

You could put the machine into Pause/Record and it would work as an amp. With so much gain on the mic input my creation produced lots of distortion but being an acoustic guitar it howled uncontrollably. I tried stuffing the guitar with the filling from some cushions but it was unsuccessful.

By the next day I had removed the neck from the guitar and fixed it to a 'solid' body. The body was in fact an old piece of block board about an inch thick. I'd read a book from the local library about electric guitars and decided to make a pickup using enamelled wire from the tube of the broken TV wrapped around some magnets I'd got from a Lego train set. Three magnets sandwiched between two pieces of thin plywood and as many turns of wire as I could fit formed the pickup. Saturday came round and I begged my mum to buy me a cheap bridge and some steel strings from the local music shop. Later that evening I had it all working, no howling but still plenty of distortion. I was hooked.

My knowledge of electronics grew, primarily through reading books from the library, and I decided to build an amplifier for the guitar. I'd studied the amps in the music shop and had some electronics hobby magazines with circuits in so I 'designed' a 50 watt solid state amplifier with Volume Bass Treble and Fuzz controls. It worked - kind of. But it didn't sound like I thought it should. The government issue school record player with its auxiliary jack input sounded better. At that time I had no test equipment and so debugging it was virtually impossible. I thought it looked cool though. A bit like the Carlsbro Stingray but with a plexi style front panel.

A while later when jamming in the school music room one evening I noticed there was what looked like an amplifier placed inside the storage alcove. On the front it said wem in big red letters and on the silver control panel the word 'Dominator'. I had no idea who it belonged to but curiosity got the better of me and I decided to plug it in and try it. I noticed it took a while before it worked - like our radiogram at home and guessed it had valves in it. As it finished warming up, accompanied by the smell of burning dust was a swell of volume as the valves began to conduct and reach their correct bias point, and my guitar sounded like it had never done before. A glorious symphony of rich chiming harmonic distortion. I was hooked again.

In 1978 I was asked to join school punk covers band The Opposites playing bass. One of the guitarists had a 100 watt Marshall half stack and a Fender Strat. He had a great sound compared to the other guitarist who was playing a Les Paul copy through a 100 watt Carlsbro Stingray (solid state) combo. I subconsciously made a mental note.

Around 1981 together with some musicians I'd met at a gig I formed a jazz rock fusion band called Actual Proof. I needed an amp to gig with and a neighbour of mine sold me my first Marshall. It was a 100 watt Master PA and cost me £50. It looked like something out of a WWII bomber with its vu meter and big chrome rack handles. The inputs were designed for microphones but the rest of it was identical to the circuit diagram I had acquired. I ripped out the input transformers and converted it into a guitar amp. It was my first 'real' amp and I gigged with it for years.

The band were quite successful - we won a national music competition held at The Royal festival Hall in London which culminated in us playing live on TV at the Albert Hall. For this gig I was offered the loan of a Marshall combo - it was brown and had four 10" speakers - a Club & Country I think. It looked a bit smarter than my rig so I went with the offer. At the sound check on the empty I plugged it in. There was a loud hum, a burning smell and then silence. With no amplifier the BBC engineers put my pedal board straight into a D.I. box and the on stage sound was terrible. Another mental note.....

Actual Proof, RFH 1983. Shaun Thompson - sax, Paul Stipetic - drums, Tony Stipetic - Bass, Cliff Brown - guitar

I was fortunate enough at school to have a woodwork and metalwork teacher who was also a musician. Like many of his era he knew about radios and valves and he encouraged me with my guitar building, and later with designing and building my first valve amplifier which would be the practical part of my Design A level. He also taught me design and drawing skills that became the foundation of my career as a design engineer. The amplifier in question was a two channel hybrid design with build in graphic equaliser, BBD delay line with modulation, FX loop and 4 button foot controller housed in a glass fibre case. The power stage was 2 x KT66 and each channel of the pre amp had a single ECC83. I'd found the transformers in a junk shop and made the chassis from steel plate and added an aluminium plate front panel. The cabinet was covered plywood. I never quite finished the amp but it building it gave me confidence and an 'A' grade in Design. I figured I needed a better knowledge of electronics and decided to go to University.

In 1983 I moved and went to university to study engineering. It wasn't at all what I expected - certainly not as much fun as school and I struggled to find a decent band to play with. I joined the Progressive Rock Society (AKA Heavy Metal and Beer Society) and I became friends with a couple of guys who managed the PA system in the students union bar. They were third year electronics students and had been experimenting with modifying Marshall amps for both tonal and reliability improvements. They shared their results with me and I started making some changes to my amp.

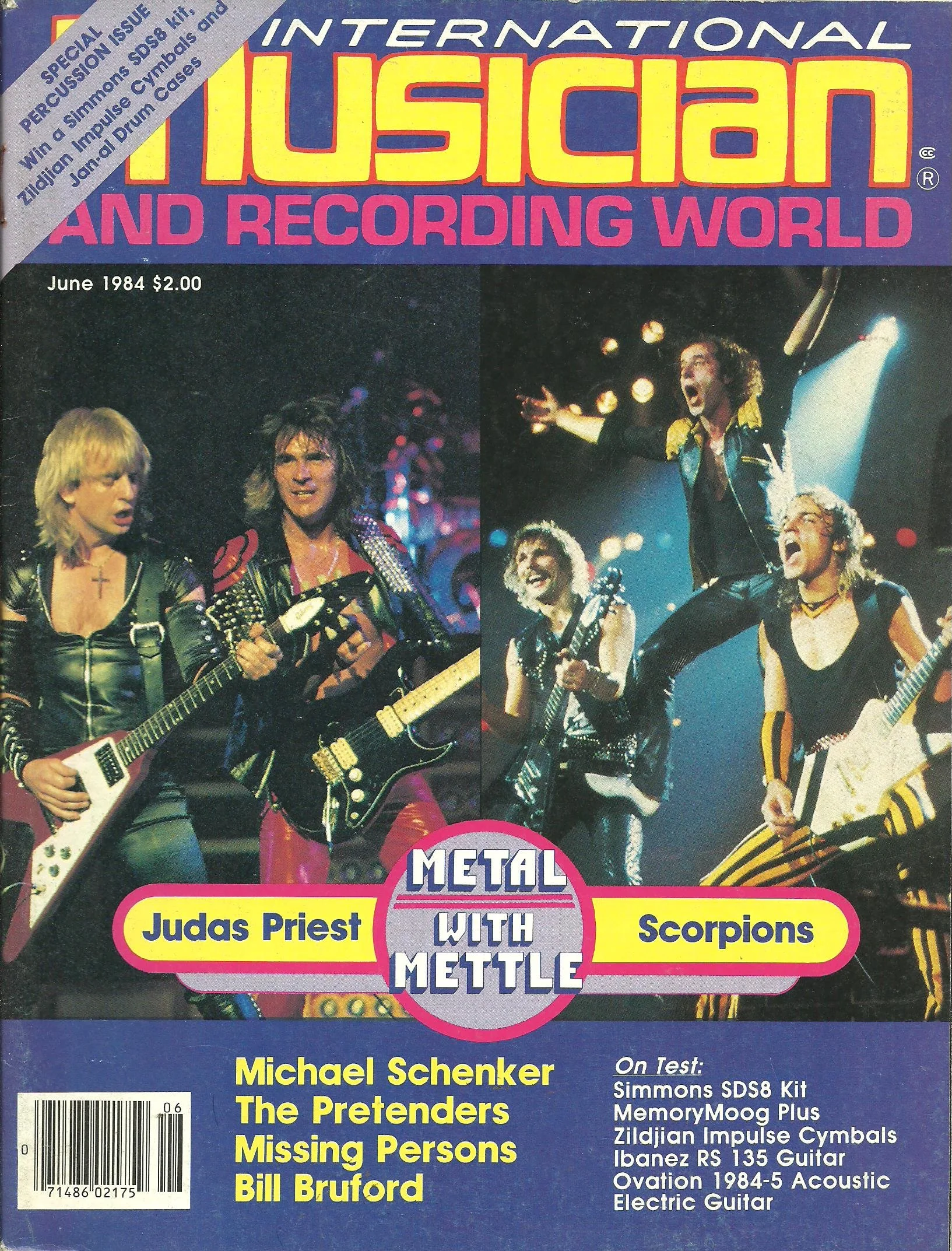

During my third term I realised that the Warwick University engineering degree wasn't for me. I'd struggled with what I now realise was a badly organised and uninspiring course so I decided I would try something else. One idea I had was to work in a recording studio so I bought a copy of 'International Musician & Recording World' and wrote a letter to every single studio advertising in there to offer them my services. A few weeks later I started to get some replies, all of them rejecting my offer, some wishing me luck and some (the BBC) recommending me to carry on with my degree.

So I then wrote to all the manufacturers who advertised in the magazine. I figured it might be a good second option and a way into other things to be building audio equipment. I must have written over a hundred letters in total. Again I got rejections from most but one company got back to me and offered me an interview for the position of Graduate Test Engineer. A week later I was in Great Sutton Street in the City of London at the factory of Soundcraft Electronics. Soundcraft had started out building PA desks in the early seventies. They were now a growing company and despite the poor economic situation in the UK were doing well because of the expanding live sound and home recording markets. They still manufacture mixing consoles to this day and are now owned by Harman. Back then they were independent and had been formed by electronics engineer and musician Graham Blyth and Led Zep sound engineer Phil Dudderidge who is now the MD of Focusrite.

Soundcraft was the perfect place for me to hone my skills in electronics. I spent a year or so in the test department, first testing and repairing modules, then moving on to testing whole consoles, some of which were very sophisticated. My electronic skills grew very quickly as did my appreciation of how products were designed to be manufacturable. The company expended and moved and then a vacancy came up working in the Test Development department which I got. The job involved programming automatic Test Equipment and designing manual test jigs for the production line. During time I made friends with R&D manager Lawrence Chong who had come from Neve. Lawrence played guitar - he had a Les Paul and a Fender Twin. Anyhow he saw my hunger for knowledge and decided to offer me a job as Junior Design Engineer.

R&D was such a cool place to work. I was surrounded by really clever engineers, hardware, software and mechanical who were great mentors, notably designers Graham Blyth, Douglas Self and Gareth Connors. I was part of a team working on the design of a digitally controlled analogue mixer for theatre, a very complex system. In my spare time I was designing and building recording equipment and guitar amplifiers in my bedroom, and playing in a band with musicians that I shared a house with. But despite having a really interesting and creative job I still had a desire to be more involved more directly with the music industry.

In late 1987 I saw an advert in Pro Sound News. Power Plant Studios in London (formerly Morgan Studios) were looking for a Technical and Maintenance Engineer. I applied and got the job and started in January 1988, working for producer Robin Millar. My job was to keep the studios in good shape technically and to design and manage the building of a new studio. I got to work on Neve, SSL and Harrison consoles, Otari, Ampex and Studer tape machines and all the best outboard gear available - Pultec, Fairchild, Urei, UA, API, Lexicon, EMT.

Compared to Soundcraft working at The Power Plant was another world. It was more demanding - clients were paying upwards of £1000 per day for a studio (in 1988!) and everything had to run like clockwork. I got to work with many famous musicians and artists and also learned to party hard and regularly! I pretty much lived at the studio and was on call with a pager when I wasn't in the building. Quite a sacrifice but it was rewarded in other ways. When there was some downtime I had free access to several state of the art recording studios. I had formed a band and we would stay all through the night recording tracks. I'd get a few hours sleep, sometimes on a couch in a studio or on the floor of the maintenance room and then do it all again the next night after a days work. I'd catch up on sleep at the weekends when I was at home on call. I was like a kid in a sweet shop, but like all good things it would come to an end.

After nearly four great years at The Power Plant, my stint working in a professional recording studio and with a great family of people sadly came to an end. The recording industry economics had taken a turn for the worst as record companies cut their budgets and focussed on CD remasters of archive material and cut the budgets for new artists. Established recording studios were closing on a weekly basis as smaller project studios became the norm. So I decided to go freelance working again for Soundcraft as a contractor, as a part time session musician and also at Andy's guitar shop in Denmark Street.

A few years later I was offered a welcome full time position in the Technical Services department at Soundcraft, where I spent five years or so travelling the world commissioning and repairing live sound and broadcast equipment. At this time I also got involved in bespoke design work for many of Soundcraft's broadcast customers. The world of broadcast expected to have custom made equipment, the R&D department were too busy working on new products - so I got the job. It was role that I enjoyed very much and came naturally to me, probably because I was used to a technical customer service role from my time at The Power Plant and at Andy's.

to be continued........